“When threatened or injured, all animals draw from a “library” of possible responses. We orient, dodge, duck, stiffen, brace, retract, fight, flee, freeze, collapse, etc. All of these coordinated responses are somatically based- they are things that the body does to protect and defend itself.”

–Peter Levine

When a woman senses danger or is attacked, her body sends automatic signals to her brain to alert her nervous system that there is a threat to her safety and a cascade of neurobiological defense responses is set off, which is often over simplified as “fight or flight”. A woman does not choose which response is initiated during an attack but may feel guilt, shame, confusion, and anger for not responding a certain way during a violent attack. Often survivors are questioned about their actions and physical responses during an attack. Even decades after a traumatic incident (such as childhood sexual abuse) a smell, sight, sound, touch, or taste may trigger memory fragments and initiate a defense cascade response for an older woman. This trauma response effectively impairs the rational, logical, thinking part of the brain, which is further confused by the attachment circuitry activated at the same time as fear circuitry, when a woman experiences violence from someone she knows and trusts. Attachment circuitry also suppresses a woman’s defense circuitry.

Freeze: The stop, look, listen stage. The woman’s parasympathetic nervous system slows her heart; meanwhile, her sympathetic nervous system gets her muscles ready for action.

Flight and Fight: The woman becomes hyperaroused. Her sympathetic nervous system prepares her to flee or, if flight is impossible, to fight. Her heart rate and breathing accelerate. Blood flows to her arm and leg muscles.

Fright: The woman panics, feels nauseous, dizzy. Her sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems are both highly active, which might make her switch actions abruptly.

Flag: The stage of despair. The woman’s parasympathetic nervous system takes over. Her heart rate and blood pressure drop. Her embodiment circuitry – the system in her brain that lets her feel her body – is compromised. She might have trouble moving. She could feel numb, separate from herself. We call this state of disconnection hypoarousal.

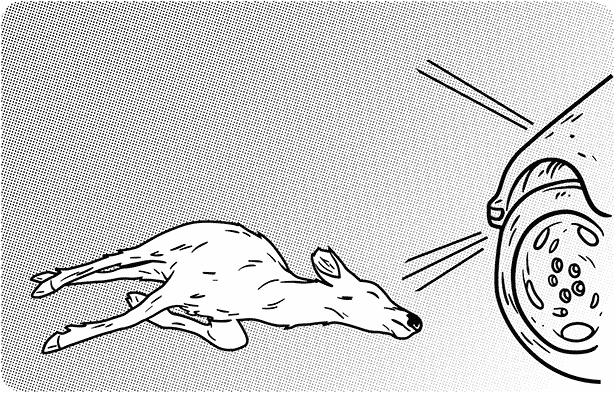

Faint: If the threat doesn’t resolve, a parasympathetic surge could slow the woman’s heart rate, decrease oxygen flow to her brain, and disrupt signals from her brainstem that maintain muscle tone. This disruption could render the woman immobile and cause her to collapse. Collapsed immobility is a term used to describe this response.

(Follette, Briere, Rozelle, Hopper, Rome, 2014; Kozlowska, Walker, McLean, Carrive, 2015; Schwartz, 2016).

Disassociation is the brain’s way of disconnecting the body from a traumatic experience, or the impacts of trauma.

It is common in trauma survivors and may be misidentified as intoxication, unwillingness to cooperate, and deception. Women who have experienced extreme fear, physical contact with the perpetrator, physical restraint and/or a perception of inescapability may also experience Tonic Immobility during an assault.

Hormonal responses to trauma may appear immediately following, several hours afterwards, or several days after a trauma (Smith, 2017).

FREEZE: Opiates and oxytocin to counteract physical pain and increase positive feelings.

FLIGHT/FIGHT: Cortisol and catecholamines to increase energy and adrenaline.

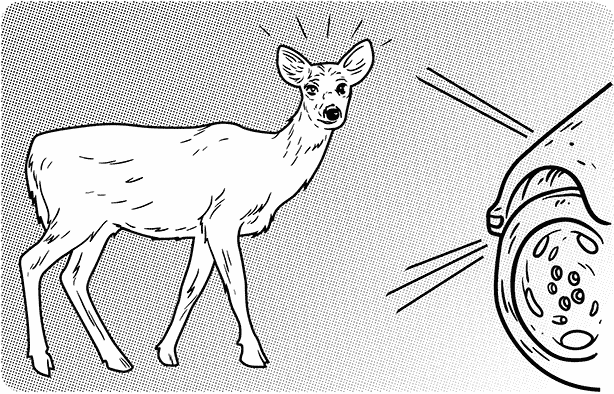

Tonic immobility (Freeze-Fright) is where a person (also seen in animals such as deer, sharks, mice, and rabbits) is extremely afraid and becomes immobile, with rigid/stiff limbs, while frozen, maintain their position. Tonic immobility may include fixed or unfocused staring, sensations of coldness, faintness and numbness or insensitivity to pain. They may have intermittent periods where their eyes are closed. A woman is frozen with fear, unable to move or talk, but may be alert or aware, or may be experiencing dissociation. This may last seconds or hours and terminate suddenly. This was previously referred to in sexual assault cases as “rape-induced paralysis.”

Collapsed immobility is sometimes called “playing dead” although, this description is inaccurate as the brain has chosen this defense. It is characterized by decreased heart rate, blood pressure, and reduced oxygen to brain, rendering the woman unable to speak or move, in addition to loss of muscle tone. This may be described by a survivor as pretending to be asleep during the attack, fainting or blacking out as she tries to make sense of a confusing and terrifying assault.

Many women experience tonic immobility during a sexual or physical assault; paralysis that lasts for seconds, minutes, even hours. The woman can’t speak or move, but remains alert. After the assault, she might blame herself for not having resisted.

A woman who has survived an assault may tell you she feels “spaced out,” “numb,” or “disconnected.” Letting her know these are natural responses that many survivors of trauma experience can help her to feel supported, less alone, and hopeful that her feelings of disconnect and numbness might change.

Food for Thought: